Utility-scale solar refers to large solar installations designed to feed power directly onto the electric grid. These huge solar installations are built by developers who sign long-term contracts called power purchase agreements with the utility companies in their areas. The power is sold at wholesale prices and sent along transmission lines to be distributed to customers.

This is different from distributed solar, which is also called “behind the meter solar,” because the electricity it generates is first used onsite by the owner, and only the excess energy is sent to the grid and counted by the customer’s electricity meter..

Read on to learn more about how solar energy is used on the utility scale.

Utility-scale solar describes large solar power plants that produce electricity for the utility grid. The utility grid, in turn, distributes the electricity to end consumers. The solar energy generated by solar power plants is sold to utility companies and other large power consumers via power purchase agreements, which we discuss later in the article.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) considers a power plant to be ‘utility scale’ if its total generation capacity is 1 megawatt (MW) or greater. There are currently over 10,000 solar photovoltaic (PV) plants that meet this definition.

Falling costs and increased demand for renewable energy mean that the utility-scale solar sector has boomed in recent years. The EIA estimates that solar is now the leading source of new electricity generation capacity, accounting for 39% of new capacity expected to be added in 2021, ahead of wind and natural gas.

While many solar power plants use the same technology as home solar systems - solar photovoltaics - they operate at a far larger scale, allowing them to generate power at an even lower cost.

Most large-scale solar plants employ technology that’s very similar to that used by residential systems; you’ll probably find little technical difference between a solar panel used on a solar farm and one atop a typical home setup. Of course, solar farms operate on a scale that is several orders of magnitude greater, which allows them to drive down per-unit costs through economies of scale.

There are two main types of utility-scale solar:

Alternatively referred to as “solar farms”, utility-scale solar photovoltaics describes the use of a large number of solar modules (solar panels) installed together to create a power plant.

The technology and configuration of solar PV power plants is quite similar to that used in residential rooftop solar panels. In both cases, the solar panels capture sunlight and use the photovoltaic process to convert sunlight into Direct Current (DC) electricity, which is then converted into Alternating Current (AC) electricity - which is the electricity homes use.

There are however, some key areas where utility scale PV differs from home solar, in terms of scale, the way they’re mounted, and their tracking technology.

Concentrated solar power (CSO) plants use thousands of special mirrors (helioscopes) to reflect sunlight onto a central collector. There, the sun’s heat energy is collected and either stored in a medium like molten salt, or used to generate electricity via a steam turbine.

Since CSP power plants use the heat energy of the sun (unlike PV plants which use light), they are often called “solar thermal plants”. They are also known as “power towers” or “salt tower plants” because of the distinctive tall towers that some CSP plants use.

A major advantage of CSP plants is that they can incorporate energy storage, allowing power generation after dark without the need for expensive batteries. However, while costs are dropping, CSP power stations are still significantly more costly than solar PV plants, and thus account for a very small proportion of solar facilities.

According to SEIA, there are nearly 10,000 utility-scale PV facilities, i.e. solar projects over 1 MW in size. The most common power plant size is between 1 megawatt and 5 megawatts (1-5 MW) in solar capacity. But it’s the big solar power stations - those greater than 50 MW in size, that account for the bulk of solar generation output.

Here are the biggest players in the utility-scale solar space; each operates over 5,000 MW in total solar capacity, according to energy intelligence company Energy Acuity:

Power purchase agreements (PPAs) are contracts that guarantee that the energy generated by a solar power plant will be purchased, usually by a utility. PPAs specify a time period for the arrangements - typically between 5 and 20 years - as well as the price that will be paid for the electricity.

PPAs are a critical element for every utility-scale solar power project. By signing a PPA, the energy operator gains confidence that it will receive an adequate return on investment, which allows them to raise the millions - in some cases, billions - of dollars required to build and operate a utility solar project.

In regulated electricity markets, renewable energy projects typically sign their PPA directly with the utility company. In deregulated markets, on the other hand, PPAs can be traded and signed with multiple off-takers (purchasers) and stakeholders.

In recent years, major corporations like Google and Amazon have been signing corporate PPAs with solar developers so that they can power their business operations with clean renewable energy resources.

As the cost of building utility-scale projects has dropped in recent years, solar PPAs are being agreed upon at ever-lower rates, which has helped make solar energy increasingly attractive to utilities and governments.

We can look at the cost of utility-scale solar two ways:

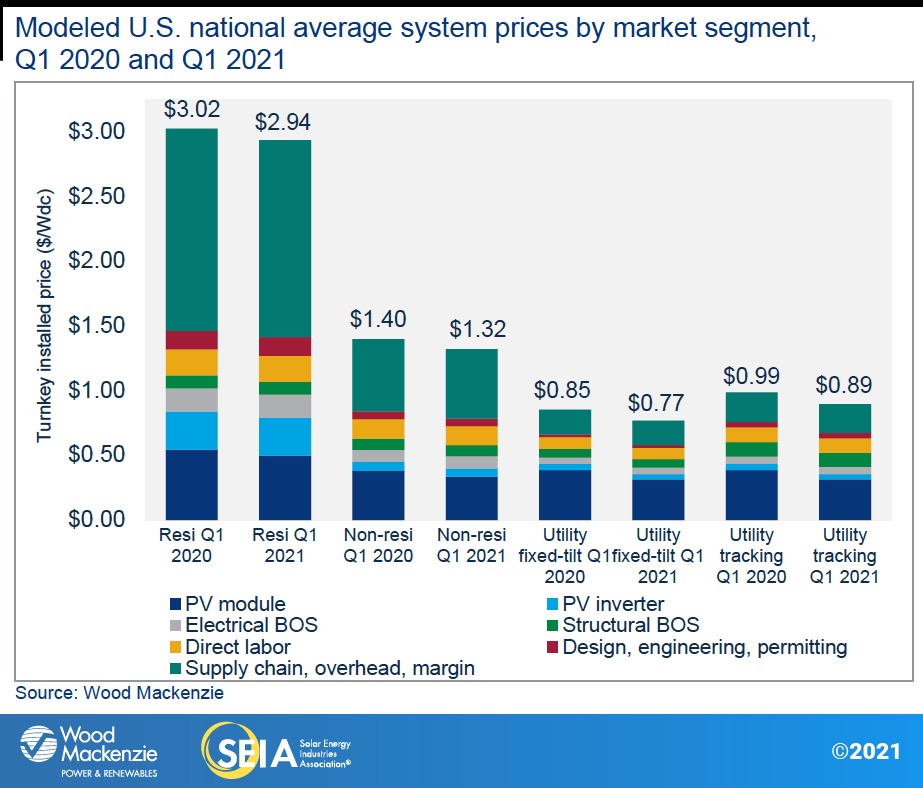

The cost of building a solar power system is measured in cost per watt of installed capacity. For Q1 2021, SEIA reported costs of $0.77 per watt for fixed-tilt utility installations, and $0.89 per watt for utility installations that incorporate tracking.

This would put a 1 MW solar power plant at between $770,000 and $890,000, while a 100 MW power plant would cost between $77 million and $89 million. These numbers are based on national averages; so expect substantial variations between projects based on scale, choice of solar panel brand, and region.

Do note that the figures discussed above, and in the chart below, are before applying the solar tax credit. This federal incentive, also known as the Clean Energy Credit, effectively reduces the cost of solar projects by 30%.

To assess the cost of utility-scale solar electricity, we can check what price solar PPAs are going for on the wholesale market.

Berkeley Labs reports a nationwide average levelized PPP of $24 per MWh in 2019, or 2.4 cents per kWh. This represented a decrease of 17% over the year before (2018) and a 80% decline since 2010.

More recently, LevelTen Energy, a renewable energy marketplace, reported an uptick in prices in 2020, with a Q3 average price of $29.2/MWh, and average prices across America’s five independent system operators of between $25.1/MWh and $36.8/MWh.

Bear in the mind that the prices quoted above are the cost of solar electricity in the wholesale market. The final price of solar for consumers will include the cost of transmission and distribution, which according to the EIA together account for nearly half (46%) the average price of electricity.

Curious about the cost of residential solar power? Get a cost estimate for your home Written by Zeeshan Hyder Content SpecialistZeeshan is a solar journalist who has long been passionate about climate issues and developed a deep interest in solar power after witnessing its successful adoption in Australia. He has previously worked as a journalist for a major news organization, covering energy, climate, and environmental stories, among other topics. He also served as an organizer for the Pakistan Youth Climate Network, an advocacy group aimed at raising climate awareness.